I have a confession: I am not a professional musician. My background is in engineering (AI, Data, Software, Product). But data is just pattern recognition, and music is the most beautiful pattern of them all. This article is my attempt to decode the “algorithm” of my Iranian-Kurdish heritage.

If you’ve ever felt a sudden lump in your throat hearing a cello, or an uncontrollable urge to tap your foot to a drumbeat, you’ve experienced what neuroscientist Daniel J. Levitin calls Music as Medicine. It’s not just poetry; it’s biology.

Growing up with an Iranian-Kurdish mother, I learned this biology early. Kurds of Iran don’t just listen to music; they metabolize it. In our house, we didn’t have “playlists”; we had survival kits. If the tea was hot and the guests were loud, there was a song for that. If the world was ending (or we just ran out of saffron), there was a song for that, too. This deep cultural emotional intelligence knows intuitively what science is now proving: music regulates the nervous system.

Let’s take a journey into the brain, through the ears of the ancient Persian masters.

The Architecture of the Soul

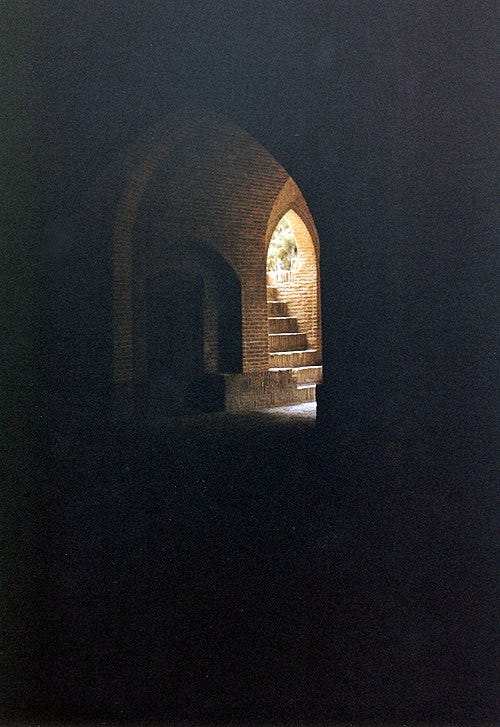

Before we talk about sound, we must talk about space. As the German writer Goethe once famously said, “Music is liquid architecture; Architecture is frozen music.” Nowhere is this truer than in Iran.

To understand the Persian music brain, you have to understand the Persian House. Iranian architecture isn’t just about bricks and mortar; it is a psychological apparatus designed to regulate the nervous system in a harsh climate. It is the physical manifestation of the exact same philosophy found in the music.

Here are the core “models” of Persian Architecture that will help us understand the music later:

Darun-gara’i (Introversion) - The Hidden Paradise

If you walk down an old alley in Yazd or Kashan, you see nothing but high, beige mud walls. It looks defensive, maybe even boring. But knock on a wooden door, step through, and you are suddenly in a technicolor paradise: a central courtyard (Sahn) dripping with blue tiles, a pool of water reflecting the sky, and pomegranate trees.

This is Darun-gara’i. It is the separation of the Biruni (the public/outer life) and the Andaruni (the private/inner sanctuary). This architecture is designed to cut off sensory overload. The outer wall blocks the noise and chaos of the bazaar (high cortisol), creating an immediate drop in blood pressure the moment you step inside. Persian music is also introverted. It doesn’t usually start with a bang (like a marching band). It starts quietly, inviting you inward, revealing its secrets only to those who have the patience to sit and listen.

The Hashti - The Decompression Chamber

You never walk straight from the street into the living room in a traditional Persian house. You first enter the Hashti — an octagonal vestibule with a low ceiling and dim lighting.

It is a pause button. A spatial airlock. It forces you to stop, adjust your eyes to the darkness, and leave the dust of the street behind before you are “worthy” of entering the main house. In music, this is the Pish-daramad (Pre-intro). It is a slow, rhythmic overture that says, “Stop thinking about your tax returns. We are entering the space of art now.”

The Iwan and the Gonbad - Reaching for the Divine

The Iwan is that magnificent, vaulted portal you see in mosques and palaces — open on one side, facing the courtyard. It usually leads to a Gonbad (Dome). These structures are often covered in Muqarnas — those complex, honeycomb-like 3D tiles.

Muqarnas are mathematical fractals. Studies in neuro-aesthetics show that looking at fractal patterns (repeating patterns at different scales, like clouds or ferns) induces a “meditative state” in the brain. Your eyes trace the infinity of the pattern, shifting your brainwaves from Beta (active/stress) to Alpha (relaxed/creative).

These domes weren’t just for looks; they were the original amplifiers. They create a natural reverb (echo) that makes the voice sound fuller and more “spiritual.” When a singer sings in a tiled dome, the frequencies resonate in a way that physically vibrates the listener’s chest cavity.

Markaz-gara’i (Centrality) - The Empty Center

In Western architecture, we often put the building in the middle of the lot. In Persian architecture, we put the garden in the middle and build the house around it. The center is empty, filled only with water and sky.

The void is more important than the solid. In Persian music, silence is as important as sound. The pauses between the notes (the “breath” of the ney flute) are where the emotion lives. You circle around the main note (the tonic) just like the house circles around the pool.

Note to the Reader: Keep these images in your mind. When we talk about “entering a Dastgah” in the next section, imagine you are walking out of the dusty street, through the cool Hashti, and sitting down in a blue-tiled Iwan, ready to listen.

Entering the Sound-House

Now that you understand the Architecture of the Soul, Persian music becomes much less scary. It is not a random collection of sounds; it is an architecture.

Here is your map to the Musical Mansion:

The Radif — Master Plan

The Radif is the total collection of this musical tradition. It is the sum of all the rooms, hallways, and gardens combined.

If Persian music is a city like Isfahan, the Radif is the City Plan. It is the master document held by the architect that says, “This is where the walls go, this is where the fountains go.”

A musician spends decades memorizing the Radif, just like an architect memorizes the laws of physics, so they can eventually build something new without the building collapsing.

The Dastgah — The Main Room

A Dastgah is a primary musical mode. There are 7 main Dastgahs. Each one has a completely different emotional temperature, just like different rooms in a house have different purposes.

The Main Halls are:

- Dastgah-e Mahur is the bright, south-facing sunroom full of windows.

- Dastgah-e Shur is the dimly lit, private Andaruni sanctuary where you share secrets.

- Homayoun is the majestic dining hall where you feel a bit regal but also sorrowful because the king is sad.

When you are in the “Kitchen” (a specific Dastgah), you cook. You don’t take a shower in the kitchen. Similarly, when a musician is in Dastgah-e Mahur, they must use specific notes. If they play a wrong note, it’s like putting a toilet in the dining room — it’s just wrong.

The Avaz — The Garden Pavilion

An Avaz is a secondary mode. It is related to a Dastgah, but distinct. Think of the Avaz as a Pavilion or Tea House built in the garden of the Main Palace. It uses the same building materials (tuning/scale) as the Palace, but the atmosphere is more intimate and specific.

To visualize this, look at the largest estate in Persian music: Shur. The Main is the central mansion. Vast, ancient, and official. Surrounding the mansion are smaller structures made of the same bricks, but designed for specific moods:

- Dashti: A rustic Shepherd’s Hut on the edge of the estate. Sorrowful and simple.

- Abu Ata: A philosophical library wing. Pleading and thoughtful.

- Bayat-e Tork: A ceremonial courtyard. Spiritual and narrative.

You wouldn’t hold a grand coronation in the Shepherd’s Hut (Dashti), even though it sits on the same land as the Palace.

The Gusheh — The Rooms

Inside every Palace (Dastgah), there are dozens of short melodic movements called Gushehs. These are the specific Rooms. A performance is a tour. The musician starts in the Entrance Hall (Daramad), establishing the mood. Then, they guide you to the “Mirror Hall” (a specific Gusheh), then perhaps to the “High Dome” (Ouj — the climax/high notes), before finally bringing you back down the stairs to the exit (Foroud).

They are constantly moving you to different “spots” within the same room to show you the emotion from different angles or different point of views.

Tahrir — The Mirror Work

If the melody is the wall, Tahrir is the decoration. When you hear a singer’s voice suddenly jump into a high, rapid, warbling sound (like a nightingale), this is Tahrir. It isn’t random shaking; it is a precise, geometric pattern of sound — much like the Ayeneh-kari (mirror work) in a Persian palace. It shatters the “light” of the note into a thousand sparkling reflections.

We now have the complete blueprint of the Persian Music City:

- The Radif: The Master City Plan.

- The Dastgahs: The 7 Grand Palaces (Systems).

- The Avazes: The 5 Garden Pavilions (Sub-systems).

- The Gushehs: The specific Rooms inside (Melodies).

- The Tahrir: The intricate Mirror Work on the walls (Ornamentation).

- The Rhythm: The way you walk through it — sometimes wandering freely (Avaz), sometimes marching to a beat (Tasnif).

The Orchestra of the Soul

Before we get to the neuroscience, you need to know the instruments. These are not just wooden boxes designed to make noise; in the Persian tradition, they are viewed as extensions of the human anatomy. Each instrument targets a specific frequency in the body, acting as a different medical device for the nervous system.

The Tar

The Tar is a plucked string instrument with a unique “double-bowl” body carved from mulberry wood. It looks like a figure-eight, or more poetically, like two heart chambers connected. This is the grandfather of the modern guitar. In fact, the word “Guitar” is linguistically derived from “Tar” (Chehar-Tar, or four strings). It was developed in the high courts of the Persian Empire and remains the primary instrument for composing the Radif. The Tar uses a very thin membrane of lambskin (specifically from a fetus or newborn to ensure purity and thinness) stretched over the bowls. This gives it a distinct, dry, and metallic resonance that lacks the “muddiness” of a western acoustic guitar.

Because the Tar is held high against the chest, its vibration physically resonates with the listener’s upper torso. Its sharp, articulate attack stimulates the Prefrontal Cortex. It is the instrument of intellect and philosophy. It doesn’t just make you feel; it makes you think.

The frets on the neck are not metal; they are made of gut string tied by hand. This allows the musician to physically move the frets up and down the neck to adjust the microtones (quarter-tones) depending on the mood of the room.

The Ney

A simple cylinder of reed with 7 holes — 6 in front, 1 in back. It is arguably the oldest still-used instrument in human history, dating back 4,500–5,000 years. The Ney is the central symbol of Sufi mysticism. The poet Rumi opened his masterpiece, the Masnavi, with the “Song of the Reed,” describing the Ney as a soul crying because it has been cut from its reed bed (separated from God). The Ney is aerophone magic. It creates a sound that is 50% tone and 50% breath (white noise).

This breathy texture is a natural nervous system regulator. The white noise frequencies mask background distractions, while the pure tone induces Alpha and Theta brainwaves (the state between waking and sleeping). Listening to the Ney forces the listener to synchronize their own breathing with the long, slow exhalations of the player, lowering blood pressure.

You don’t blow into a Persian Ney like a recorder. You place the sharp metal edge of the instrument between your two front teeth (the interdental method). The sound is actually created by the air hitting the teeth and the metal edge simultaneously inside the mouth. It is incredibly difficult to master; students often pass out from dizziness in their first months of practice.

The Kamancheh

A spherical, spiked fiddle with a small body made of walnut or mulberry, covered in fish skin or python skin. It is played vertically, resting on a spike on the player’s thigh. The Kamancheh is the ancient ancestor of the European Violin. It traveled the Silk Road, influencing the Rebab in the Arab world and eventually the Violin in the West. In 2017, its craftsmanship and performance were inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list. While the violin screams, the Kamancheh whispers. Its sound is nasal, warm, and heartbreakingly human.

The frequency range of the Kamancheh almost perfectly overlaps with the human female voice. This activates Mirror Neurons in the brain — the same neurons that fire when you see someone else crying. It bypasses logic and hits the empathy centers directly. This is why it is the primary instrument for Avaz-e Dashti (The Good Cry).

When a violinist plays, they move the bow and keep the violin still. When a Kamancheh master plays, they move the bow and spin the instrument itself to meet the bow. Watching a master like Kayhan Kalhor is like watching a dance between the wood and the horsehair.

The Tombak

A goblet-shaped hand drum carved from a single solid block of wood (usually walnut or mulberry), covered with camel or calf skin. For centuries, drums were seen as “background” instruments. The Tombak changed this. In the 20th century, masters elevated it to a solo melodic instrument, proving that rhythm alone could carry a narrative. The Tombak has the widest tonal range of any hand drum. It can produce a deep, sub-woofer bass (Tom) and a sharp, whip-crack snap (Bak).

This is the tool of Neural Entrainment. The Tombak provides the “grid” that the brain latches onto. Its deep bass notes resonate in the gut (Vagus nerve stimulation), offering a sense of grounding and safety (“I am here, I am solid”), while the intricate finger snaps keep the brain alert.

The modern Tombak technique involves using all ten fingers independently. There is a specific technique called the Pelang (The Leopard’s Claw), where the player snaps three fingers in rapid succession against the rim, creating a sound exactly like a heavy rainstorm hitting a tin roof.

The Neuroscience of the Quarter-Tone

Why does this music make you cry/dance/sleep? It’s all about the Microtones.

In Western music (think piano), we have fixed steps: C to C#. In Persian music, we have notes in between the cracks of the piano keys. These are the Sori (slightly sharp) and Koron (slightly flat).

Your brain is a copycat. When you hear a steady rhythm, your neurons start firing in sync with it. This is Neural Entrainment. Persian music often starts with a free-rhythm intro (Avaz) that demands active attention, then drops into a rhythmic beat (Reng or Tasnif). A slow, steady drumbeat (like a heartbeat) signals the Vagus Nerve to lower your heart rate and blood pressure. It tells your body, “The tiger is gone; you can digest your kebab now.”

Those quarter-tones (Koron/Sori) are the secret weapon. Because they don’t exist in Western tuning, your logical brain (Prefrontal Cortex) can’t easily predict them. It gives up trying to analyze the math and lets the sound slide straight into the Amygdala (the emotional center). This “limbic bypass” allows the music to access deep emotional states — grief, longing, ecstasy — without you having to talk about them. It’s sonic therapy. It validates pain rather than trying to “fix” it.

Knowing this, we can move from theory to prescription. Let’s imagine a few scenarios where we can apply this “medicine” to your daily life, matching the Dastgah to the neurochemical need.

The Radif as a Bio-Hack

Think of the Radif not just as a collection of songs, but as a toolkit for regulating your internal state. Just as you might use caffeine for energy or chamomile for sleep, you can use specific Persian modes to “hack” your brainwaves and steer your consciousness where it needs to go.

The Good Cry

Picture a late Tuesday night. It is raining against the window, and you feel a heavy, inexplicable weight in your chest. You don’t need cheering up; you need release. This is the realm of Avaz-e Dashti. Often called the “sorrowful bride” of the repertoire, Dashti does not try to fix you. Instead, it mimics the very human sounds of weeping and moaning, but elevates them into art.

When you listen to Dashti, your brain recognizes this empathetic signal and triggers the release of Prolactin — the very same hormone your body produces to soothe you after a bout of crying. It is the musical equivalent of a friend sitting quietly in the rain with you, holding your hand until the storm passes. It is the Persian soul’s answer to the deep, cathartic ache of the Blues or Adele’s “Someone Like You.”

The Morning Dopamine Hit

Now, imagine the opposite: it is early morning, the sun is streaming across the floorboards, and the world feels full of potential. You need a soundtrack to match this waking energy. This is when you turn to Dastgah-e Mahur.

Mahur is the sound of sunlight. Resonating closely with the Western Major scale, it is heroic, optimistic, and undeniably bright. As the melody climbs, it signals your brain’s reward centers to flood your system with Dopamine — the molecule of motivation and anticipation. Listening to Mahur is like drinking a double-shot of espresso; it wakes up your spirit and prepares you to conquer the day, much like the opening notes of Vivaldi’s “Spring” or The Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun.”

The Warrior’s Awakening

Now, shift to the golden hour of sunrise. The day ahead is daunting, and you need more than just caffeine; you need courage. You turn to Dastgah-e Chahargah, the “Warrior.”

Unlike the gentle sadness of Dashti, Chahargah is explosive. Its intervals are wide, distinct, and ancient, hitting the ear with the force of a trumpet blast. This sound stimulates your sympathetic nervous system — the “fight or flight” mechanism — but channelled through the structure of music, it doesn’t create panic; it creates power. It floods your system with adrenaline, making you feel triumphant before the battle has even begun. It is the sonic equivalent of the Rocky theme song or a Hans Zimmer epic, designed to make you feel invincible.

The Mystic’s Memory

It is an autumn evening, and the sun is setting, casting long, golden shadows. You are overcome by a wave of nostalgia — a longing for a past love or a time that has slipped away. The prescription is Avaz-e Bayat-e Isfahan, the “Mystic.”

Isfahan is sophisticated and deep. It uses a scale similar to the Western harmonic minor but twists it with a specific microtone that the Portuguese would call Saudade — the presence of absence. This specific frequency activates the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center. It pulls forward autobiographical memories, allowing you to dwell in a state of sweet, philosophical longing. It is a candlelit dinner for your soul, echoing the complex emotions of a Miles Davis jazz ballad — elegant, dark, and profoundly beautiful.

The Nostalgic Sunset

Shift the scene to an autumn evening. The sun is setting, casting long shadows, and you are overcome by a wave of nostalgia — a longing for a childhood home or a love long gone. In this twilight hour, the prescription is Avaz-e Esfahan or Dastgah-e Segah.

These modes are spiritual and deeply distinct, utilizing specific microtones that don’t exist in Western piano music. These “in-between” notes bypass your logical defenses and activate the Default Mode Network in your brain — the area responsible for autobiographical memory and self-reflection. It triggers a feeling the Portuguese call Saudade, a complex, beautiful mix of joy and sadness. It makes you think of your ancestors and the passage of time, echoing the reflective depth of Leonard Cohen or “Yesterday” by The Beatles.

The Anxiety Antidote

Consider the chaos of a stressful midday. Your mind is racing, your phone is buzzing, and your brain is trapped in “Beta wave” static. You need an anchor. You need Dastgah-e Homayoun.

Homayoun is majestic, solemn, and regal. It does not plead; it commands. Its gravity is so immense that it acts as a neurological breaking mechanism, forcing your scattered brainwaves to slow down into the relaxed alertness of “Alpha waves.” It is authoritative and grounding, essentially telling your anxiety to sit down and behave. It carries the same heavy, stabilizing emotional weight as the first movement of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata.”

The Spirit’s Anchor

Finally, imagine it is mid-day. The office is chaotic, your phone is buzzing, and your stress levels are spiking. You need to stop the noise. You need Dastgah-e Nava, the “Spirit.”

Nava is the antidote to chaos. It is unique because it lacks the “wailing” or intense emotional peaks of other modes. Instead, it is chant-like, moderate, and repetitive. When your brain is scattered in high-stress “Beta waves,” Nava acts as a cognitive anchor. Its orderly structure signals safety to the amygdala, lowering cortisol levels and forcing your mind into a state of focus. It is not music for dancing; it is music for breathing. It functions like a medieval Gregorian Chant or the ambient post-rock of Sigur Rós, turning the noise of the day into a quiet, sacred space.

Clarity in Chaos

We have all faced the paradox of productivity: you need music to drown out the silence, but most playlists are a trap. If the music is too boring, you fall asleep; if it is too emotional, you lose focus. When you are staring down a mountain of complex data — whether studying for the bar exam or building a financial model — you need a sonic environment that is as structured as the work you are doing. This is the domain of Dastgah-e Rast-Panjgah and Dastgah-e Mahur.

These modes work because they speak the language of order. Relying heavily on major-like intervals, they mimic the famous “Mozart Effect,” presenting your brain with patterns it recognizes as “resolved.” Unlike the emotional modes that pull at your heartstrings with yearning microtones, Mahur and Rast-Panjgah are structurally rigid and confident. They don’t make you feel sad; they make you feel clear. By removing the need for your brain to process musical tension, they free up glucose for your prefrontal cortex, the center of logic. To unlock this state, seek out instrumental Rengs or Chaharmezrabs featuring the Tar or Santur. The rapid, mathematical precision of these instruments acts like a metronome for your thoughts, driving you forward with relentless, joyous logic.

Silencing the Monkey Mind

The sun has gone down, but your mind is still racing. The “monkey mind” is chattering, replaying the day’s anxieties, and sleep feels miles away. You need to lower your heart rate and coax your brainwaves from the alert buzz of Beta to the restorative drift of Theta and Delta. For this, you turn to Avaz-e Abu Ata.

Abu Ata is known as the “Philosopher” of the Persian modes. It is wise, meandering, and calm, devoid of the hysterical highs found in other systems. Traditional performances often linger in the lower range of the scale for extended periods, utilizing low-frequency sounds that evolution has trained us to interpret as safety signals. It avoids the screaming climaxes that excite the nervous system, instead offering a gentle, downward melodic spiral. For the ultimate sedative effect, listen to a Ney solo in Abu Ata. The breathy, airy sound of the Persian flute introduces a natural “white noise” that masks the terrifying silence of the room, acting as a sonic blanket that tucks your consciousness into bed.

Returning to Natural Time

Even when we manage to escape on vacation, our brains often stay trapped in the city — stuck in “work mode,” anticipating urgent emails and deadlines. To truly detach and reconnect with “natural time,” you need a sound that breaks the rigid grid of modern life. You need the open horizons of Bayat-e Tork or Avaz-e Afshari.

These modes carry the DNA of the nomad. Bayat-e Tork, with its deep roots in Sufi storytelling and the call to prayer, triggers a sense of vast, open space. It feels like a journey, tricking your brain into looking at a horizon rather than a screen. Afshari, on the other hand, possesses a distinct instability — a “wobble” — that feels raw, human, and organic. It is the antidote to the digital world. Play a quiet Setar solo in Bayat-e Tork while walking on a beach or hiking through a forest; the intimate, acoustic vibration will help strip away the armor of the city and return you to yourself.

The Programmer’s “Flow State” Protocol

For those who live in code, the challenge is unique. You need to enter the “Zone” — that elusive state of flow where hours pass like minutes — but you can’t have lyrics disrupting the language centers of your brain. You need a soundtrack that is as complex and logical as the system you are building. This is where Dastgah-e Nava becomes your engine.

Nava is the “Hacker” of the Persian repertoire. It is widely considered the most cerebral and mathematical of the Dastgahs, avoiding catchy hooks in favor of repetitive, chant-like motifs that slowly mutate over time — much like a recursive function. This creates a “While Loop” effect in your mind, a stable, running process that grounds you without creating emotional spikes that break concentration. Its moderate, serious tone keeps your brain in a high-Beta state of alert focus, making it feel like you are solving a puzzle rather than listening to a song.

Pro Tip for Devs: If you are debugging a nightmare race condition and feeling panic, switch to Homayoun. It imposes order on chaos. If you are just grinding out boilerplate code, Nava is your engine.

Where to Start: The Masters

If you search for these modes, start with the giants of the tradition to ensure you get the pure “medicine.”

- The Voice: Mohammad Reza Shajarian. (The undisputed master).

- The Soul: Kayhan Kalhor. (Master of the Kamancheh and Silk Road Ensemble member).

- The Architect: Hossein Alizadeh. (Master of the Tar and composition).

Building Your Own “Persian Music Pharmacist”

We’ve covered the theory, the neuroscience, and the prescription. But as an AI engineer, I don’t want to manually look up these prescriptions every time my mood changes. I want an agent to do it for me.

I decided to build “Dr. Radif” — a simple AI tool that takes your environment (mood, weather) and translates it into a search query for the correct Persian musical system. Unlike a simple if/else script, we use LangChain and OpenAI so the system can understand semantic nuance (e.g., knowing that "heartbroken" requires the same cure as "grief").

https://github.com/chrisshayan/The-Neuroscience-of-Persian-Music/blob/main/drradif.py

You do not need to speak Persian to understand this. Your amygdala speaks the language of vibration. So next time you feel a mood swinging in, you can run the code, find the right Room in the mansion, and let the biology of sound do the rest.

The Geometry of Joy

We started this journey with neurons and code. We looked at the mechanics of the ear and the physics of the Tar. But if you strip away the science and the Python scripts, you are left with one simple truth: Presence.

The genius of the Persian Master — whether the architect of the Blue Mosque or the composer of the Radif — was their understanding that humans suffer because we are trapped in the past or anxious about the future. The architecture was built to enclose you; the music was composed to hold you.

The Algorithm of the Bazaar

In my day job, I work at the intersection of Banking and AI. In many ways, modern banking is the ultimate “Biruni” (the noisy public exterior). It is transactional, binary, and stressful. It deals entirely with the anxiety of the future — risk, interest, savings, debt.

We often build banking apps that function like the busy, dusty streets of the bazaar: optimized for transactions, but hostile to the human spirit.

But what if we designed our digital world with the wisdom of the Andaruni (the inner sanctuary)?

What if an AI banking assistant wasn’t just a calculator, but a “Dr. Radif” for financial health? Imagine an AI that doesn’t just tell you you’re over budget (stress), but recognizes the context of your spending. An AI that offers the digital equivalent of Avaz-e Abu Ata (calm wisdom) when you are panic-selling, or the motivating structure of Mahur when you are saving for a goal.

The Code, The Capital, and The Clay

The great Persian mathematician and poet, Omar Khayyam, understood this balance better than anyone. He was a man of data (an astronomer) by day and a mystic by night. He knew that while we can calculate the movement of the stars — or the compound interest on a loan — the only reality that truly matters is the human experience of the Now.

As Khayyam wrote:

“Ah, fill the Cup: — what boots it to repeat How Time is slipping underneath our Feet: Unborn TO-MORROW and dead YESTERDAY, Why fret about them if TO-DAY be sweet!”

This is the ultimate lesson the Radif offers to those of us building the future of technology. We are not just coding for efficiency; we are coding for humanity. Whether we are building a recommendation engine for music or a credit scoring model for a bank, our goal should be to reduce the noise, creating a “Hashti” — a decompression chamber — where the human on the other side of the screen can feel safe, understood, and seen.

The Persian House is the Clay. The Capital is the structure. The Music is the Empathy poured into it.

So, whether you use the code above to hack your focus, or you go back to building the next generation of digital banking, remember: the goal isn’t just to process the data. The goal is to remember that, like the geometric tiles on the dome, we are all part of a beautiful, infinite pattern.

Drink the wine of the sound. Be happy for this moment. This moment is your life.